One of the formative experiences of my childhood:

My grandfather was a stubborn, combative midwestern WASP who helped start the Chicago options exchange. He was a ball turret gunner in WWII, nickname “Sharpie,” because he was always ready with a quick-witted barb, always a little edgier than his milieu of dedicatedly bland, upstanding citizens from the distant Chicago suburb of Geneva, IL.

His cohort were well-to-do lifelong Dems; Library Anglos, historical society supporters, staunchly moral and naturally drawn to the task of building community and tribal memory, and thus deeply repelled by the slightest whiff of political selfishness. He was no different. He died years before the 2016 election, but he would’ve hated Trump, just as my grandmother did, due to his bombast and bad manners.

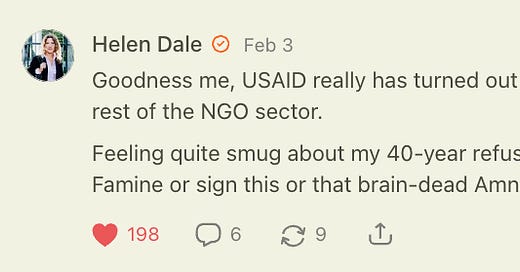

But he did something once that upset everyone in the family, something that clearly presaged the Trump Era. On Christmas, my archetypical Boomer artist parents—in fact extremely archetypical as a Jewish/Protestant pairing in not only academia but theater academia—would linger around on Christmas waiting for my grandfather to cut them a check, which he always begrudgingly did, his “sharpie” flack ever-increasing as he got older. One year, I’d been induced by my parents to ask for a donation from him for my participation in a local 30 mile bike ride to support Multiple Sclerosis. More recently, there is a growing consciousness that the money contributed to these sorts of events—e.g. Susan Komen “pinkwashing”—seems to vanish into the void, to become the currency of patronage farms for self-dealing parasites and other creepy NGO swindle machines. But at the time, everyone, even antisocial leftists, participated in these events with gusto and pride.

So I was induced to approach my grandfather at the right time during Easter and ask him, bright eyed and bushy tailed, for a large donation for my arduous MS ride. I must’ve been around 12 or 13 years old, and I didn’t really understand what I was asking for—why would someone give you money to do a bike ride, but you didn’t keep the money, and instead it went to some abstract population suffering from some abstract disease, none of whom you’d ever met? It didn’t make any sense.

My parents knew the ask would be a point of conflict, it was a test, probably encouraged by my mother, who, like many lapsed Jews, was in an endless battle of empathy-signaling with her Christian parents-in-law—supposedly so moral yet so deficient in so many ways that would be obvious to the perennially oppressed Jewish people. They shuffled me forward and I made the big ask.

My grandfather became cross and silent in that air-disturbing way that only fathers and grandfathers can be. The air disappeared from the room. “No,” he said.

It completely shocked me. I had been conditioned to believe that charity bicycle rides were the very definition of goodness. Anyone who would refuse CHARITY, no less charity related to a HEALTHY FITNESS ACTIVITY, on behalf of THEIR OWN GRANDCHILD was comically evil. Darth Vader grade evil. Evil just for the sake of it. The type of person who would gladly torture animals and leave grocery carts willy nilly in the parking lot. The absolute opposite of a responsible Christian grandfather. How could this be happening?

I choked up with bewilderment and forced out a “why?” tears dripping down my face.

“Because I don’t believe in that sort of thing,” he responded.

My parents squibbled around like spooked hyenas, but that was the end of it. There would be no more discussion. He sipped his bourbon and sat in his chair and read something, probably the New Yorker, and tuned out the awkwardness. Later we probably searched for Easter eggs in the garden, I still remember the feel and the smell of the tomatoes in the garden, those little orange follicles that stick to your fingertips and later when you wash your hands they release their scent of pure summer.

For years afterwards, his refusal was constantly referred to with great pain, one of those colossal betrayals that haunts families for decades and never gets resolved, even after the guilty is dead. I am particularly susceptible to such resentments—I stopped speaking to my other grandparents for other betrayals and never went back.

But with this grandfather, even back then, I can remember my own pain over his blunt denial dissolving even as my parents’ festered and grew. There was just something about it—something brave, that I couldn’t help but admire. The totally brazen refusal to play along—the confidence in one’s own convictions even when everyone else believes you’re stone cold evil, the “against us” in the mind of our collective BPD. And not just the conviction not to bend, but the open disgust about being asked to bend in the first place. There’s divinity in anti-collectivism—an irrational self sacrifice just for the sake of it—that I think reaches up towards God.

And, of course, he ended up being entirely correct.

These nonprofit rackets are in fact societal cancers corroding the fabric of beautiful historic human-centric places like Geneva, IL. Public/private corruption systems, probably propped up by USAID or equivalent, feeding off the gentle goodness of the natural midwesterner in order to generate instability, profit, and global grayness for the benefit of definitely-not-religious-Christians. I remember once walking down the street on a beautiful fall Sunday in Geneva and being shocked by how many healthy beautiful shining hand-holding families were out strolling under the fiery leaves—like a time machine back to a time before cars and phones and crime, when everyone was just out and connected and together in the town square. You could almost see the connection between them in the air, it was so thick as to become a substance, the natural state of what humanity can be when not interfered with. I haven’t been back in awhile but I can promise you that connectedness is a lot less thick in Geneva today. And there are a lot more charities and a lot more charity rides.

I never got to know my grandfather well, probably in part because he was meant to serve as a Grinch figure. He had had four handsome, smart, white suburban sons, but among them they had only had two grandchildren, my cousin Louise and I. I couldn’t tell you why that happened, besides to say that it is certainly a very Boomer phenomenon, and thus almost certainly related to the sterilizing self-hatred that crept into the white American population around that time, a self-hatred that would go basically unacknowledged until Trump.

He died when I was 15. I remember him crumpled up in the hospital bed, barely able to speak or move, but his eyes were glued on me. Fixed. His pale blue eyes, very pale, almost white, this very prototypical midwestern wasp sort of eye blue paleness. His eyes always had a deeply piercing quality, like they were looking through you, or more like you were looking through him. And I remember him staring at me and not looking away. Saying nothing, just staring—like an inanimate bump on a log with two pale blue portals to the afterlife. It became awkward for everyone else because he was staring so hard and unblinkingly, but he didn’t seem to care what anyone thought. I flittered around uncomfortably, and ultimately left the room (one of my biggest regrets to this day). But I remember interpreting it as a sign, as a statement: “It’s on you now, motherfucker.”

Great tribute to Sharpie. What a legend. Stubborn, combative, disagreeable traits are critical to civilization and seem to be inherited - it’s on us motherfuckers now.

“The totally brazen refusal to play along.” Brilliant observation.